Cecilie Norgaard

In conversation with Barbara Pflanzner, Academy Studio Program, Creative Cluster on April 4, 2024.

You once stated that you view painting as a system that is exclusively reflected by itself. Can you elaborate on that?

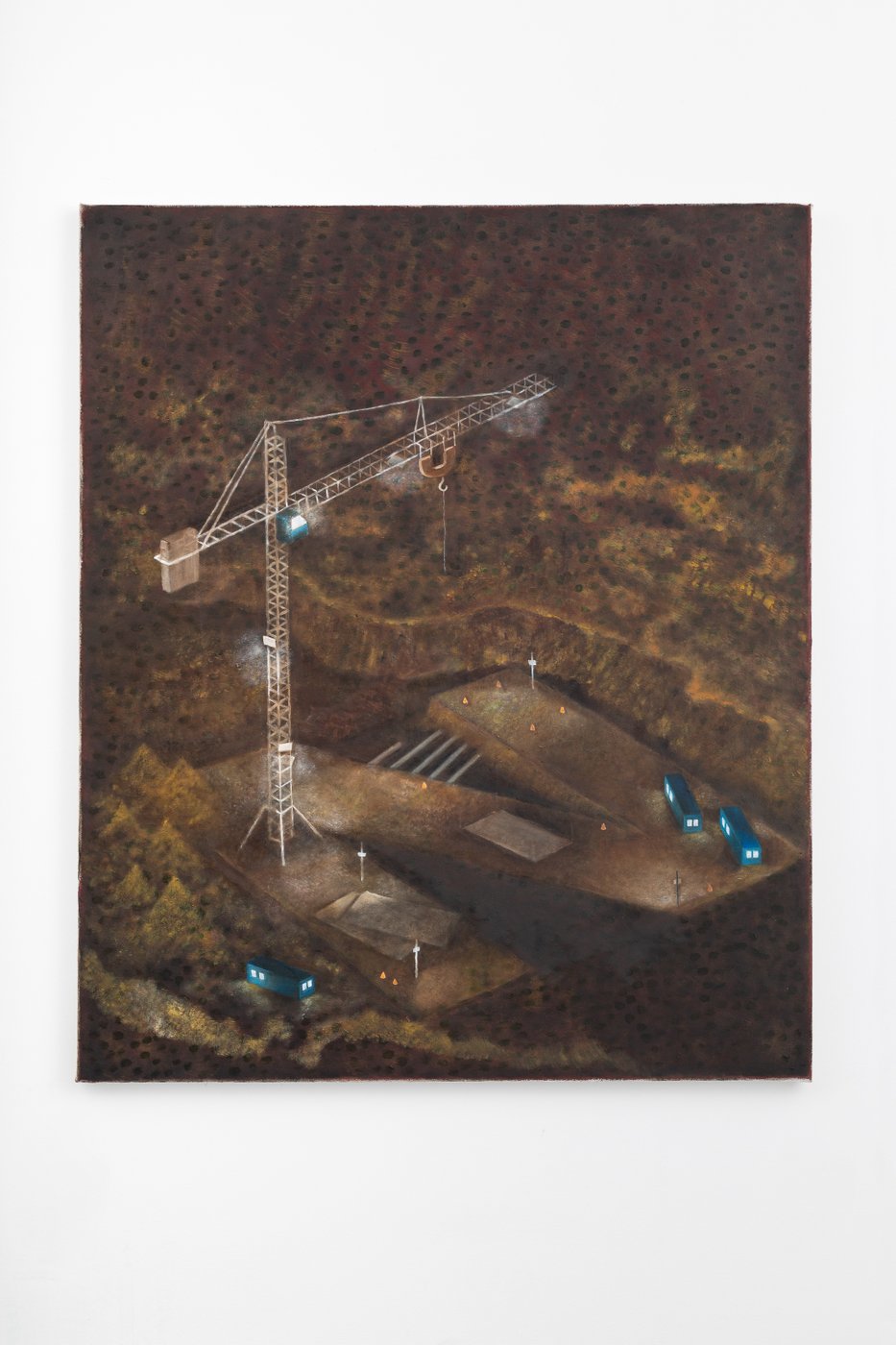

I don’t want to state that as a general claim, but for me, I find it the only interesting way to approach it. I am thinking about the “medium” of painting – a medium that can allegorize and metaphorize itself and in that way demonstrate awareness of itself. In one of my last exhibitions, for instance, the idea was to create a symbolic relationship between painting and sport; a parallel or allegory between what it means to work in the art world and what it means to be a player in a game or competition. The pictures sought connections between the chosen topic and the examination of the medium. For example, there were paintbrushes on the soccer field, or there was a digital clock or a score display that didn’t show the time or the result of the game but the format of the painting. Another picture showed a sports field, but it was painted in such a way that it was reminiscent of historical modernist paintings. In another exhibition, I had the idea of depicting the medium of painting as a truck, looking at each oil painting as a big, heavy, macho vehicle and then subsequently thinking about what goods it transports.

You spend a lot of time researching and writing, before you start on working on a new work series. How do you choose your topics and motifs?

For me, painting is not a very gestural or expressive activity. It’s always based on an idea that shifts from project to project. The research can be theoretical, but usually, when I read theory, it rarely informs the work in the idea phase but comes in later. The research is more about looking at images – like stock images or pictures of objects that interest me – and about trying to find a source image that can represent whatever the idea is.

Your motifs invite us to immerse ourselves in the pictorial world, but at the same time a lot remains unclear. To what extent do you see a narrative moment in your work, or is that not so relevant for you?

That’s a common question. For me, the narrative is in the conceptualism, and the question of why the paintings were made the way they were or why they represent what they represent. There is a narrative that holds the work together and grounds it. But at the level of the individual painting or the moment that many people describe, where they feel invited in and a kind of process of identification takes place, there is no story. Of course, I find it interesting that this process of identification takes place at all.

Some of your pictures remind me of paintings from art history periods such as the Renaissance, especially in terms of color or technique. Are there any art historical models, or does this not play a role in your work?

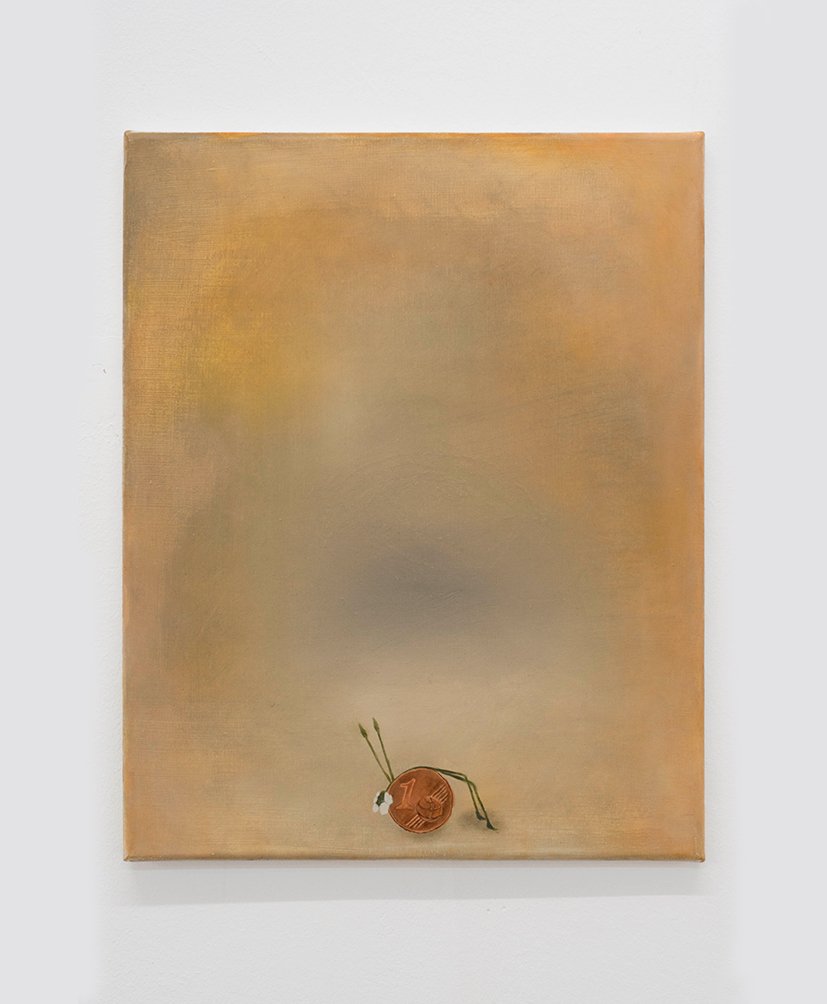

I recently visited the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, where they exhibit a lot of Renaissance painting. In terms of content, it’s all religious, which I in itself don’t find super interesting. But structurally, how the images are composed, how the artists managed to divide the pictures into different ontological layers, for example the sacred on one level and the profane on another, and how such shifts happen within one and the same picture, that’s a source of a lot of inspiration. It’s inspiration that is structural and at times allegorical, and less about specific depictions of stories and characters. The use of tempera in my work is a material reference to old techniques of mixing and using paint, but beyond that, my use of color is more intuitive than referential. I like when colors aren’t clean. I feel a certain skepticism towards cleanliness and a greater “belief” in mud.

Your works also often show several layers and are precisely balanced in terms of structuring the space.

I’m totally interested in decorative patterns, and how one can abstract them to patterns of behavior and vice versa. I often use and depict elements from public spaces as they are often structured in a patterned way – one that can easily translate to something decorative.

You always work on many pieces at the same time. What do you like about working this way?

It seems to be the only way I can work. It has to do with several things: I start something and then I need time to figure out what I want it to become; I need other places where I can simultaneously direct energy. When I’m working on one painting, I can abstract it or take a part of it and work it out in another. That way it becomes a juggling act that I really enjoy. I think if I concentrate too much on one painting, it can become its own character to the point where it looks too singular, too independent from the other pictures.

You always also create a connection and a system within the work group, then?

Yes. I always emphasize how elements in one picture shift or take on a different meaning so that these basic signifiers change their meaning and at the same time weave the pictures together. When I started working on a series of paintings depicting trucks, I wanted to integrate something turquoise in every single painting, and this element would then shift from piece to piece, for example a round globe or screens set in a circle, or small squares that could be either screens, or depictions of paintings. I called it “symbolic knowledge”, because I figured that’s what’s being imported and exported by “painting”.

At the beginning of the Studio Program, one of your goals was to work with sound. Have you been able to realize that?

I have a performative whistling band with my friend Nanna Friis called More to Life. We just performed in LA. So I guess the answer is yes!

A whistling band is not that common – can you explain in more detail how you came up with this concept and what you whistle?

We’re both very good whistlers. And to be honest, it seems that people are very enthusiastic about good whistling. We’re thinking about how to put it in an art context and make it interesting. In principle, I don’t find it that interesting when someone, just because they’re good at something, shows it to a group of people that then gets excited. We’ve done various experiments with it in the past. For instance, my friend Melanie Ebenhoch once curated an exhibition at Galerie Martin Janda and invited me to whistle. I recorded a song in an edition of three and put it on sale. I think there’s critical potential in using something as ubiquitous and unspecialized as whistling and presenting it as a specialized, unique commodity. I’m interested in the economics of the art world and of finding ways to highlight the absurdity of the designation of value that takes place within this context. Another interesting aspect is that, in fact, watching other people whistle is a pretty intimate experience. One really has to concentrate and thus comes very close to the performers. Somehow, people remain kind of ambivalent about whether they should laugh or be touched. There’s something to it.

You’ve already shown your work in several group and solo exhibitions in galleries and art spaces. Are there any plans for exhibiting in the near future?

Yes, for my next exhibition Die installierte Reale at Rinde am Rhein in Düsseldorf, I’m collaborating with my friend, the artist Sanna Helena Berger. We have wanted to work together for some time. Basically, our aim is to link painting with other, less marketable works. Both of us fundamentally develop a kind of institutional critique in our work, albeit in very different media. I only work with painting, the only medium Sanna Helena avoids out of principle and commercial reasons. It’s interesting for us to see how we can force painting to collaborate and link with other material, how it can “lend” its surface to other forms of work. After this exhibition, I’m going to present works in a solo show in the artist-run space wieoftnoch in Karlsruhe. Then I’ll be presenting work at CHART in Copenhagen and a solo presentation at Vienna Contemporary with Matteo Cantarella, with whom I just had a show in Denmark. And after that, a group show in Belgrade is planned.