Chiara Bartl Salvi

In conversation with Barbara Pflanzner, Academy Studio Program, Creative Cluster, March 21, 2024.

You’re a visual artist, performer, and choreographer. Do you have a background in dance yourself?

Yes, when I was very young, my mother took me to dance lessons twice a week across the German border to nearby Freilassing, where I learned ballet and jazz dance. There was a performance every year, where I gained stage experience early on. Later, I started teaching children aged eight to ten there and rehearsing my own choreographies with them, which were then performed at these shows. The first choreography I taught them was to the track “Super Bass” by Nicki Minaj. That was a great, formative time for me.

It sounds like your career as an artistic performer has grown very organically.

Exactly. During this first professional experience, I was also part of the dance department at the music high school in Salzburg. Every year, there were “tryouts,” which was a choreographic format where you had to develop a piece of choreography and present it to an audience on a big stage, namely the Arge Kultur. For my final project, I worked with the two performers Alexandros El Greco and Luis García “Fruta” from SEAD Salzburg, which was the first time I collaborated with two professional dancers. That was an experience that strongly influenced my artistic development.

In your artistic work, you combine various dance styles, integrating classical dance elements such as tap dancing. Can you explain your approach to your performances?

My artistic approach combines movement and sound in a symbiotic relationship that consciously contrasts different dance styles and sounds. I aim to invite audiences to question this relationship, which may seem self-evident not only in choreography but also in everyday life. For years, I’ve been intensely exploring tap shoes as a medium and sound-generating body prosthesis. The performance 1, 2 Step (until the loop ends) uses tap shoes as the starting point for the choreographic and sonic material. In this work, I delve into questions of reproducibility, authorship, and viral trends in today’s media landscape, and more specifically, how movements and sound are reproduced and interpreted in this context. The collaboration with sound artists is central to this exploration.

One often feels familiar with certain movement sequences, which is because they originally come from choreographies in well-known pop music videos. Which of these movements and sequences pique your interest?

I’m inspired by music videos, live performances, and the sounds of various female artists, especially those whose work I have been following for years. Artists like Beyoncé are central for me, inspiring me undoubtedly due to their precise yet powerful movements and their strong connection to rhythm. I find the integration of traditional dance forms such as flamenco into pop culture, as Rosalía does it, particularly remarkable. Through this fusion, she not only bridges the past and present but also connects different cultural worlds. Artists like FKA Twigs, Rihanna, Britney Spears, or the Pussycat Dolls have also left their mark on the pop music landscape and on me in their own ways.

I would like to come back to sound, given its essential role in your work. Could you outline how it’s produced?

I usually record the sound first. That means I take my tap shoes and tap in a rhythm. Then I go to the studio of my sound partner, the artist Paul Ebhart, with whom I’ve been collaborating intensely for a long time, and record it professionally. Once I’ve developed a movement to accompany it and tried out a few canons with the performers, Paul incorporates a canon into the initial rhythm. Additionally, I record a short pop-style track, either with him or with my colleague Titus Probst, in which I sing myself. I perform it live during my performances, or it’s looped with a loop station. The loop is always included in my performances because it’s the easiest way to turn a monophonic sound into polyphony.

You like to perform with other performers in your pieces. How can one envision the process of creating a piece?

The creation process of a performance can be very diverse and depends on my specific ideas and the people behind the project. For example, I developed and choreographed 1, 2 Step (until the loop ends) on my own and then rehearsed the movement material with my longtime friend Rebecca Rosa Liebing. What we worked on together was the joint exploration of the respective spatial architectures in order to find the way through the exhibition space or gallery for the performance. This collaborative exploration allows us to organically adapt the performance to the specific space and strengthen the interaction between us performers. Overall, flexibility and collaboration are central to the creation of my pieces, whether I work alone or with other performers.

So this work is specifically designed for the immediate location?

Yes, exactly. The first edition of 1, 2 Step was conceived for the Kunstverein Eisenstadt, where we made a tour through the architecture of the exhibition space, starting from the first floor through the staircase to the foyer, and then back up the hallway. The second edition was for Außenstelle Kunst Wien, the third took place at Contemporary Matters in Seestadt, and the fourth took place at the Schiller Museum in Weimar. It was important to me that Rebecca and I also engaged with the artistic works present on-site. Therefore, we always scheduled enough time to carefully look at the exhibitions in the institutions and to discover which references we had and which we could find.

Both in your diploma project What else can we do but play? and in the work What remains for us but linger? revolving stages are central protagonists. What interests you about the interaction with objects of this kind, and does a performance change through this interplay?

Through my art studies at the Academy, I’m interested in classical stage technology and its mechanical characteristics, especially revolving stages and their historical development. I read that the Volkstheater Vienna still had a turntable until the 1980s, manually operated by stagehands. Revolving stages were developed to enable quick stage and scene changes. In my diploma project What else can we do but play? a children’s carousel serves as the foundation and movement mechanism for a revolving stage. This performance was based on institutional independence resulting from the COVID-19 lockdowns and the associated restrictions. Consequently, I had to focus on our movement possibilities in the urban environment and found inspiration at the playground as a meeting zone and social experiential space where children explore their body perception, motor skills, and social behavior. Using a mobile aluminum platform, I transformed the carousel in Weghuber Park in Vienna into a revolving stage and made it the setting for my performance. The carousel is located directly opposite and has a view of the Volkstheater, which I find a beautiful reference.

I’ve noticed that children often enjoy repurposing playground equipment and don’t always use them as intended. I find that beautiful. In connection with this, I linked my choreographic work to the rotating surface of the carousel, which greatly influenced the performers’ self-perception, as they had to deal with sensations like dizziness, centrifugal force, gravity, and disorientation.

I developed the choreographic movement material for the performance based on the painting Children’s Games by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. I translated scenes from the painting into gestures and incorporated them into the performance. Bruegel’s painting depicts a lot of children playing – playing tag, dancing, marching in procession, playing with spinning tops, windmills, and dolls, and repurposing objects to become their toys. Many of these games are familiar to us, while others seem more like imitations of adults. At this point, I had already finished the design and plan for the mobile rotating and lifting stage for the performance What remains for us but linger? that I originally intended to realize as my diploma project, but its production was complicated due to COVID-19. So the carousel ultimately served as a dummy for it.

You premiered What remains for us but linger? at WUK in February 2024. What’s the piece about, and how did it go?

Firstly, I want to thank the Academy, which strongly supported this project. Thanks to my scholarship for the Studio Program and the Mentoring Program, I was able to successfully realize it. Special thanks also go to the Creative Cluster, which allowed me to use its gym for rehearsals for weeks.

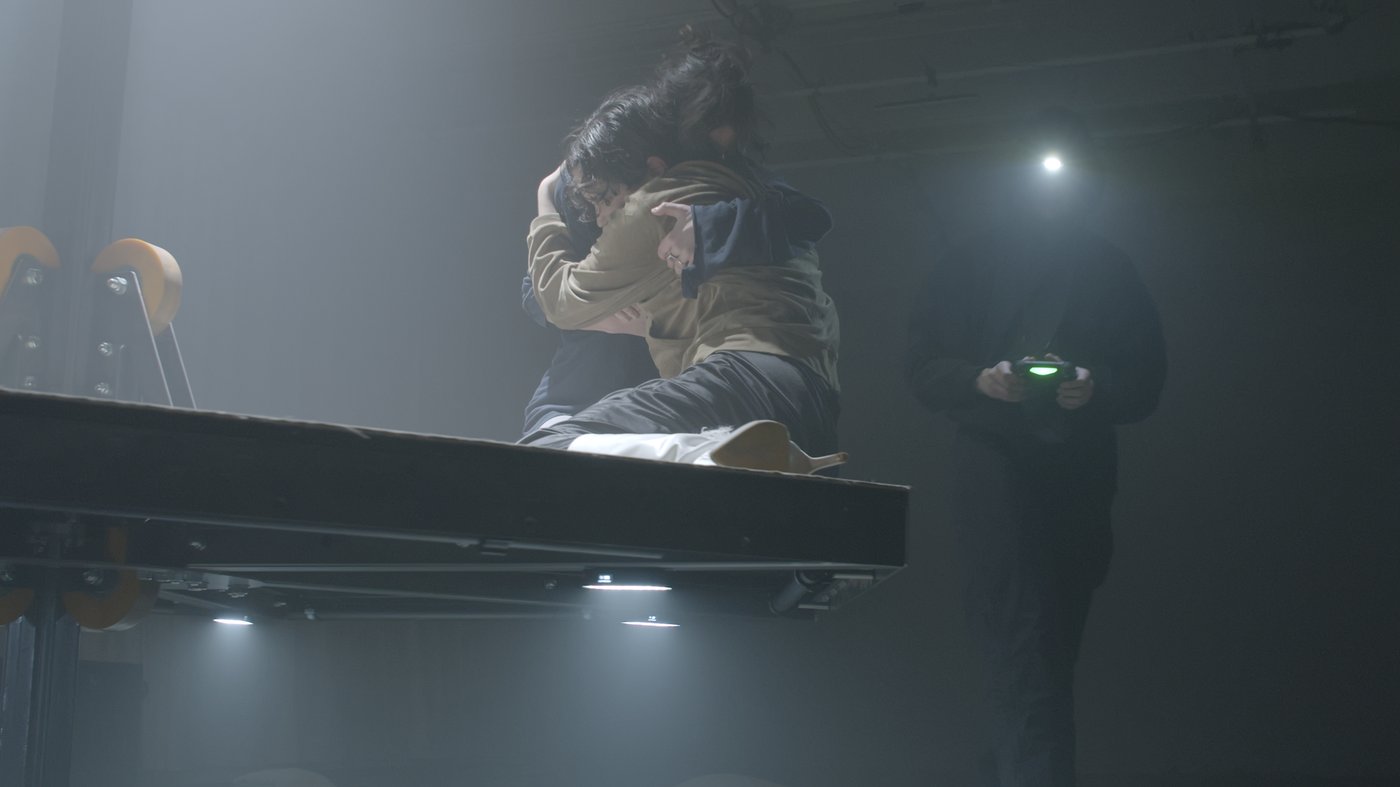

The mobile rotating and lifting sculpture was developed collectively over a period of four years and completed in 2022. It consists of a hexagonal platform that can rotate around its own axis and move up and down. I then began to develop the performance, in which three performers interact with it and control it live during the performance, manually or with a gaming controller. The choreography was developed considering the motor capabilities of the sculpture. The title What remains for us but linger? illustrates both the long wait that accompanied the project’s development during the peak of the pandemic, including the challenges of applying for funding and procuring materials during.

Furthermore, the performance addresses lingering and the process of mutual approach among the three performers in an undefined space, their routines, interactions, and individual speeds. Different realities and utopias coexist simultaneously and intermingle. With this work, I would like to invite the audience to reflect on the dynamics between bodies and spaces, the interactions between movement and sound, and the overcoming of boundaries. The interaction between the performers and the rotating and lifting sculpture takes place in three phases: In the first, the sculpture is purely driven by the performers’ force. This phase illustrates direct physical control and the interaction of the performers with their environment. In the second, the sculpture is controlled live by the performers via a gaming controller. This phase marks a shift towards technologically mediated interaction. In the third phase, the sculpture performs a choreography previously loaded onto the controller. This phase emphasizes the fusion of human control and automated processes – the performers retain control over the device, but in a way predefined by the program.

The work involved a large team, which I can’t leave unmentioned, and to whom I also want to express my gratitude: Patrick Winkler, Alba Rastl, Arno Gitschthaler, and Felix Huber worked together on the conception. Arno and Felix were responsible for the technical implementation and supervision. The performance on the rotating and lifting sculpture was initiated by my project management; I also conceived and directed the choreography. The performers were Elena Francalanci, Rebecca Rosa Liebing, and me. Paul Ebhart was responsible for the sound, Lukas Gschwandtner, Alba Rastl, and Patrick Winkler designed the stage set, Oscar Ott was in charge of the lighting design, and Ada Karlbauer wrote the text. I especially want to thank the two wonderful performers, Elena and Rebecca, Patrick, and also my former mentor from the Mentoring Program, Michikazu Matsune. I greatly appreciated his feedback and assistance. Also, I want to thank Andreas Fleck, the head of WUK Performing Arts, for the invitation.

In that case, you were able to make good use of the Studio space, which delights me! Now that this major project has been completed, do you already have plans for the near future?

What will follow? I don’t know. Of course, a heartfelt project has now come to an end. My wish would be to tour a bit with it now. In 2025, I’ll be presenting a piece with Leon Leder (Asfast) at Rakete in Tanzquartier Vienna, and I’m now trying to immerse myself in it and start the research process.